HOME / ABOUT  "Upstairs" is a work of fiction, but the events

that inspired it are all too real. On Sunday, June 24th, 1973, the fourth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising in New York, a gay bar known

as the Up Stairs Lounge in the "Gay Triangle" area of the French Quarter of New Orleans was set ablaze by an arsonist.

Wooden stairs leading to the bar's only entrance were doused in lighter fluid and set alight. Twenty-nine people perished in the fire itself,

and another three succumbed to their injuries afterward, bringing the death toll to 32. Fifteen of the 35 survivors were injured.

It remains the deadliest attack on an LGBTQ population in US history.

In months prior to the fire, the Up Stairs Lounge had been used as a temporary home for the fledgling New Orleans congregation

of the Metropolitan Community Church, a denomination founded in 1968 in Los Angeles to serve the LGBTQ community.

Many of the patrons in the bar that night were MCC members, including the pastor and associate pastor of the New Orleans MCC,

who both perished in the blaze. It was the third fire at an MCC church during the first half of 1973, following earlier arsons in Nashville

and Los Angeles. The church's Los Angeles headquarters was destroyed on January 27, 1973, five days after the U.S. Supreme Court

announced its momentous decision in the case of Roe v. Wade. On July 27, 1973, a month after the Up Stairs fire, the San Francisco

MCC was also heavily damaged by arson. "Upstairs" is a work of fiction, but the events

that inspired it are all too real. On Sunday, June 24th, 1973, the fourth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising in New York, a gay bar known

as the Up Stairs Lounge in the "Gay Triangle" area of the French Quarter of New Orleans was set ablaze by an arsonist.

Wooden stairs leading to the bar's only entrance were doused in lighter fluid and set alight. Twenty-nine people perished in the fire itself,

and another three succumbed to their injuries afterward, bringing the death toll to 32. Fifteen of the 35 survivors were injured.

It remains the deadliest attack on an LGBTQ population in US history.

In months prior to the fire, the Up Stairs Lounge had been used as a temporary home for the fledgling New Orleans congregation

of the Metropolitan Community Church, a denomination founded in 1968 in Los Angeles to serve the LGBTQ community.

Many of the patrons in the bar that night were MCC members, including the pastor and associate pastor of the New Orleans MCC,

who both perished in the blaze. It was the third fire at an MCC church during the first half of 1973, following earlier arsons in Nashville

and Los Angeles. The church's Los Angeles headquarters was destroyed on January 27, 1973, five days after the U.S. Supreme Court

announced its momentous decision in the case of Roe v. Wade. On July 27, 1973, a month after the Up Stairs fire, the San Francisco

MCC was also heavily damaged by arson.

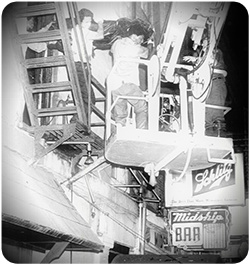

Located on the second floor of

a three-story building at the corner of Chartres and Iberville Streets, the Up Stairs Lounge had only one entrance, up a wooden flight of stairs.

That evening the bar held a free beer and all-you-can-eat special, attracting a crowd of almost 125 regulars. About 60 patrons stayed

after the event ended, most of them MCC members there to plan an upcoming benefit for the Crippled Children's Hospital to be held in the

bar the next week. 23-year-old David Gary played piano, and bartender Buddy Rasmussen served drinks. Following an altercation,

two men, David Dubose and Roger Nunez, were kicked out of the bar. Upon exiting, one of them threatened to "burn them all out".

At five minutes to eight that evening, the buzzer downstairs, usually used to signal an arriving cab, was rung. The bartender, Buddy,

asked a regular, Luther Boggs, to yell down that no one called a cab. Luther opened the steel fire door leading downstairs, and the oxygen-starved

fire on the wooden stairwell exploded into the room, engulfing it in flames that quickly spread to the bar's draperies and tablecloths. Located on the second floor of

a three-story building at the corner of Chartres and Iberville Streets, the Up Stairs Lounge had only one entrance, up a wooden flight of stairs.

That evening the bar held a free beer and all-you-can-eat special, attracting a crowd of almost 125 regulars. About 60 patrons stayed

after the event ended, most of them MCC members there to plan an upcoming benefit for the Crippled Children's Hospital to be held in the

bar the next week. 23-year-old David Gary played piano, and bartender Buddy Rasmussen served drinks. Following an altercation,

two men, David Dubose and Roger Nunez, were kicked out of the bar. Upon exiting, one of them threatened to "burn them all out".

At five minutes to eight that evening, the buzzer downstairs, usually used to signal an arriving cab, was rung. The bartender, Buddy,

asked a regular, Luther Boggs, to yell down that no one called a cab. Luther opened the steel fire door leading downstairs, and the oxygen-starved

fire on the wooden stairwell exploded into the room, engulfing it in flames that quickly spread to the bar's draperies and tablecloths.

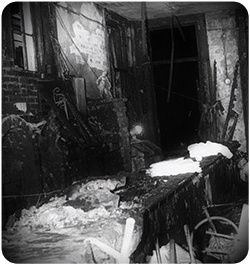

Moving quickly, Buddy managed to lead thirty-eight people out through a hidden exit behind the bar. Some thirty others were left inside the

second-floor club, stymied by unmarked emergency exits and barred and shuttered windows. A few managed to escape through the narrow bars,

jumping to the sidewalk below, some in flames. Reverend Bill Larson, pastor of the New Orleans MCC, made it partway through

the bars on one window, but got stuck. He burned alive, crying "Oh, God, no!" as he died in front of horrified, helpless witnesses on the sidewalk

below; his charred remains were visible to onlookers for hours afterwards, as the police and fire departments conducted their investigation.

Moving quickly, Buddy managed to lead thirty-eight people out through a hidden exit behind the bar. Some thirty others were left inside the

second-floor club, stymied by unmarked emergency exits and barred and shuttered windows. A few managed to escape through the narrow bars,

jumping to the sidewalk below, some in flames. Reverend Bill Larson, pastor of the New Orleans MCC, made it partway through

the bars on one window, but got stuck. He burned alive, crying "Oh, God, no!" as he died in front of horrified, helpless witnesses on the sidewalk

below; his charred remains were visible to onlookers for hours afterwards, as the police and fire departments conducted their investigation.

MCC assistant pastor George "Mitch" Mitchell managed to escape, but returned to the fire when he realized his boyfriend, Louis Broussard,

was not with him; both men died in the fire, their remains were found clinging to one another. George Matyi also escaped but went back

to rescue more trapped patrons; his body was discovered embracing those of two other victims. Thirty-five people survived due to Buddy's

heroic efforts leading them out of the bar to the roofs of the French Quarter, hoping from roof to roof until they found a safe way down.

The fire, which lasted only 17 minutes, killed more gays and lesbians in America than any other incident to date, and was the deadliest

fire in the history of New Orleans, a city which has burned to the ground twice.

The fire exposed an ugly streak of homophobia and bigotry in a city which had long turned a blind eye to the vices of the French Quarter.

It was the first time New Orleans had to openly confront the existence of its own gay community, and the results were not pretty.

Initial news coverage omitted mention that the fire had anything to do with gays, despite the fact that a gay church in a gay bar had been torched.

What stories did appear used dehumanizing language to paint the scene, with stories in the States-Item, New Orleans' afternoon paper,

describing "bodies stacked up like pancakes" and that "in one corner, workers stood knee deep in bodies... the heat had been so intense,

many were cooked together". Other reports spoke of "mass charred fles" and victims who were "literally cooked".

It was here that a July 1

memorial service was held, led by Troy Perry, founder and then head of the MCC denomination. The services were attended by 250 people, including the

state's Methodist bishop, Finis Crutchfield, who would die of AIDS fourteen years later at age 70. The news media gathered outside the front door

waiting to photograph the mourners exiting. When the service concluded those in attendance were offered an exit in the back, in order to keep

their anonymity. In a moment of solidarity, which many believe was the beginning of an openly gay movement in New Orleans,

the Congregation decided to walk out the front entrance to face the press.

Although called on to do so, no elected officials in all of Louisiana issued statements of sympathy or mourning. Even more stunning,

some families refused to claim the bodies of their dead sons, too ashamed to admit they might be gay. The city would not release the remains

of four unidentified persons for burial by the surviving MCC congregation members. They were buried in mass graves at Potter's Field,

New Orleans' pauper cemetery. No one was ever charged with the crime, and it remains unsolved. It was here that a July 1

memorial service was held, led by Troy Perry, founder and then head of the MCC denomination. The services were attended by 250 people, including the

state's Methodist bishop, Finis Crutchfield, who would die of AIDS fourteen years later at age 70. The news media gathered outside the front door

waiting to photograph the mourners exiting. When the service concluded those in attendance were offered an exit in the back, in order to keep

their anonymity. In a moment of solidarity, which many believe was the beginning of an openly gay movement in New Orleans,

the Congregation decided to walk out the front entrance to face the press.

Although called on to do so, no elected officials in all of Louisiana issued statements of sympathy or mourning. Even more stunning,

some families refused to claim the bodies of their dead sons, too ashamed to admit they might be gay. The city would not release the remains

of four unidentified persons for burial by the surviving MCC congregation members. They were buried in mass graves at Potter's Field,

New Orleans' pauper cemetery. No one was ever charged with the crime, and it remains unsolved. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HOME / WHY A MUSICAL Some of the victims of the Upstairs arson fire that inspired my current play had children. This is one of those obvious things that is somehow forgotten, since, for the last 30 years or so, most gay men haven't tended to procreate. But, though it was a gay bar, the Up Stairs Lounge had many patrons who'd attempted to have families that aligned with the norms of the day, even as they continued to search for the love that would fulfill them.A son of one of the victims contacted me recently. His letter was heartbreaking. One of the most difficult aspects of this project has been the immense responsibility to do right by the victims and their families and friends, many of whom still carry this loss. The man who contacted me was just a little boy when he lost his father to an intentional act that he calls "murder". He said that he's "still waiting" for his father to come home. From the other details in his note, I believe that he is, and that his entire life has been defined by that waiting. One thing he asked in his letter was "Why a musical?". It's a fair question. Here, edited, was my response.

This isn't a musical like "Sound of Music". It's not a comedy, though there are some comedic moments. It's dark, but it's also not a "dark comedy". The music is used to set a mood and to explore the emotional state of the characters. I'm grateful to all of the people directly impacted by the fire who have reached out to me. While we say that the fire is "forgotten", it is only forgotten by mainstream culture. There is a community of survivors, loved ones, historians, and artists who have kept the memory of the fire alive for 40 years, even as some of them try their best to forget. I'm thankful for their work, and humbled by my own small role in carrying that legacy. |

HOME / MEMORIAL  Partners Joe William Bailey and Clarence Josephy McCloskey, Jr. perished together. McCloskey's sisters and two nieces

attended the Memorial Service. His niece, Susan, represented McCloskey in the Jazz Funeral.

Partners Joe William Bailey and Clarence Josephy McCloskey, Jr. perished together. McCloskey's sisters and two nieces

attended the Memorial Service. His niece, Susan, represented McCloskey in the Jazz Funeral.

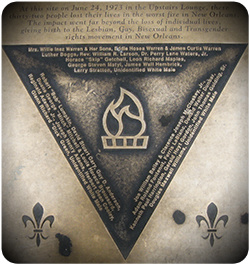

Duane George "Mitch" Mitchell, assistant MCC pastor. He had escaped through the emergency exit with a group led by bartender Douglas "Buddy" Rasmussen, but ran back into the burning building trying to save his partner, Louis Horace Broussard. Their bodies were discovered lying together. Mrs. Willie Inez Warren of Pensacola later died from burns suffered in the fire. Her two sons died inside the bar, Eddie Hosea Warren and James Curtis Warren. Pastor of the MCC, Rev. William R. Larson, formerly a Methodist lay minister. Dr. Perry Lane Waters, Jr., a Jefferson Parish dentist. Several victims were his patients and were identified by his x-rays. The full list: Douglas Maxwell Williams; Leon Richard Maples, a visitor from Florida; George Steven Matyi; Larry Stratton; Reginald Adams, Jr., MCC member, formerly a Jesuit Scholastic; James Walls Hambrick, who had jumped from the building in flames, died later that week; Horace "Skip" Getchell, MCC member; Joseph Henry Adams; Herbert Dean Cooley, UpStairs Lounge bartender and MCC member; professional pianist David Stuart Gary; Guy D. Anderson; Luther Boggs, teacher, who died two weeks later, notified while hospitalized with terrible burns that he had been fired from his job; Donald Walter Dunbar; professional linguist Adam Roland Fontenot survived by his partner, bartender Douglas "Buddy" Rasmussen, who led a group to safety; John Thomas Golding, Sr., member of MCC Pastor's Advisory Group; Gerald Hoyt Gordon; Kenneth Paul Harrington, Federal Government employee; Glenn Richard "Dick" Green, Navy veteran; Robert "Bob" Lumpkin. Four men were buried in Potter's Field: Ferris LeBlanc (later indentified), and three persons only identified as Unknown White Males. The city refused to release these bodies to the MCC for burial. |

HOME / CHARACTERS Based on historical details and thorough research, and named in homage to the victims, the characters and events presented in "Upstairs" are fictional and composite in nature.

* * *

BUDDY - A bartender. Buddy is a charismatic good looking, well-loved and respected guy. Everyone at the Up Stairs lounge knows Buddy and he gets a lot of phone numbers left on napkins. Based on bartender Buddy Rasmussen, who saved 35 people from the burning bar. ADAM - Buddy's boyfriend. A scholar and an alcoholic, Adam is an East-coast intellectual who feels out of place in New Orleans and outshone by Buddy. He covers his feelings of jealousy, inadequacy, and alienation in caustic wit and in copious gin-and-tonics. AGNEAU - A young gay man from rural Louisiana. Raised by his fiercely religious uncle, Agneau has come to the Up Stairs Lounge to indulge base desires he can't reconcile with his upbringing and beliefs. His awkward attempts to fit in barely hide a seething rage. UNCLE - Agneau's homophobic, misogynist uncle, whose folk theology of sin and punishment has controlled Agneau's imagination for all his life, even after Uncle's own death. His ubiquitous, ghostly presence shows the madness of Agneau's interior world. INEZ - A young black mother of two grown men, Inez looks after them with a fierce protectiveness twisted by her own difficult past. Pregnant twice from a wealthy white man she thought she loved, she raised the boys to avoid heartbreak by never committing. LOUIS - Inez's oldest son, Louis spent his childhood pampered by his father. He learned piano and French at a young age, but was cast suddenly into poverty when his father split from Inez. His mom's grief, pregnancy, and poverty gave him an air of sardonic cheer. HORACE - Inez's youngest son and a former hustler, Horace is a born-again Christian who considers his past life to be well behind him as a result of his monogamous relationship with Mitch and his active membership in the local Metropolitan Community Church (MCC). MITCH - Assistant pastor of the New Orleans MCC, and partner to Horace. Mitch is a decent man who was once married to a woman, with whom he had two children. He regrets the degree to which he hurt his wife when he left her, and wants to avoid another such mistake. MERCY - A popular New Orleans drag performer who, as an old friend to Buddy, has agreed to perform this night at a benefit that Buddy's best customers are organizing for the MCC. Larger than life and proud of it, Mercy demands respect for herself and her friends. REGINALD - Marcy's dresser and assistant, Reginald, is an intellectual and introverted gay man, still coming to terms with his sexuality, and his way of presenting himself to the world. He is prone to chatter when he's nervous, yet rarely says what really needs saying. |

HOME / INTERVIEW In June of 1973, an arson fire destroyed the Up Stairs Lounge in New Orleans, killing 32 of its predominately gay male patrons. Despite its grim status as the most fatal crime against LGBT people in U.S. history, the event remains obscure, its victims largely unknown and unremembered. Their stories were silenced years ago by an uncaring media, an uncomfortable church parish, a city's economic imperative to protect its reputation, and a cowed gay community's desire to avoid a fight. No one was ever convicted of the crime.My play endeavors to help break break the decades-long silence around this act of unspeakable violence, bringing new light to the tragedy and a new voice to its victims. But I'm not alone. Also coming soon is Clay Delery's forthcoming book "The UpStairs Lounge Arson: Thirty-Two Deaths in a Louisiana Gay Bar, June 24, 1973" a history of the fire and its aftermath, on which much of my play is based. In this conversation with Delery, we discuss violence, the South's history of silence, and the reasons the Up Stairs fire still matters today.

* * *

(Wayne Self) Most of the relatively short histories one reads about the fire today focus on the aftermath, and the silence, indifference, and even ridicule that followed the tragedy. Why do you think that is? (Clayton Delery) There were no proclamations of outrage or sadness from politicians at any level. There were no arrests. There'd have been no memorial service if the Metropolitan Community Church, a primarily LGBT Christian denomination whose New Orleans church counted many of its members among the dead, hadn't sent their founder, Troy Perry, into town to organize one. Troy Perry and the other clergy and activists had a difficult time even finding a location for a service. When they asked for cooperation, they were turned down by clergy and leadership from the Catholic, Episcopal, Baptist and Lutheran churches. Only one Unitarian congregation and one unusually liberal Methodist congregation were willing to cooperate. In the end, they went with the Methodist church, because it was in the French Quarter, and close to the scene of the fire. The spirit of the Stonewall Riots, which had happened only three years earlier, almost to the day, had not yet come to New Orleans, where some LGBT leaders (who, let's admit, were mostly G at that time), joined political and religious leaders in a conspiracy of silence around the fire. We are both Southerners. Do you find that the South was slower to embrace the "coming out" movement? If so, why? In a way, the whole city was staying in the closet about the fire. This arrangement protected tourism for the city, protected religious leaders from having to choose between compassion or condemnation, and protected New Orleans's gay community from "coming out" of the quiet arrangement they had with the NOPD and entering a political and legal fight for equality that they didn't think they could win. Many people were comfortable with homosexuality being thought of as simply another vice in a city known for profiting from vice in myriad ways. Of course, today we still find lots of very good reasons to stay in the closet. I don't just mean the celebrities and other notables who don't come out, but our refusal as a community to discuss our own problems with the larger society. Drugs. Health concerns. Our own racism and internalized homophobia. We still keep quiet about these things. And, in some other countries, of course, the closet is still very much in effect. Sometimes with good reason. We tend to think of history as moving toward progress, but that's just not the case. It moves in fits and starts. It's easy to get comfortable. In New Orleans, at that time, things on the surface weren't as bad as they had been in New York in 1969. It had been several years since there had been a mass raid of a bar or a gathering place. Gay people lived in relative peace. So, in some ways, people were comfortable. There was no immediate reason for a Stonewall type event. But the fire revealed a deep current of homophobia. Did things change after the fire? Some people say it was a galvanizing moment for the community, and some say that it was completely ignored. The truth, I think, lies somewhere in the middle. It did reveal a need for a more organized, more vocal community, but the New Orleans response was never going to be like a New York response. It was quieter, and more in line with New Orleans sensibilities. Why do you think the fire still matters today? Is it a cautionary tale? Is there anything inspiring or motivating in the tragedy? I think there is inspiration to find in the tragedy. Some of the stories of the night of the fire are so heroic and profound. So many responses are compassionate and brave. Seeing these victims as individuals, I think, reveals a great deal to respect, admire, and be inspired by. I think every victim of violence should matter. It's an error to fail to honor the victims at the Up Stairs Lounge while we honor so many others. What we choose to remember, what moves us to action, says something about ourselves. Do we want it said, for example, that the hundreds dead each year from urban handgun violence mattered less than the suburban children killed at Sandy Hook? Or that the soldiers who died in Afghanistan mattered less than the soldiers who died in Iraq? Of course not. The same is true here. It's right that we honor Matthew Shepherd, for example, but some of the victims here were no less young, no less active, no less wonderful. I also think it matters because of its place in context. The Up Stairs Lounge was a known meeting-place for the Metropolitan Community Churches, and the leaders of that organization saw it as another in a series of fires at their churches. There was a great deal of concern at the time that the fires were part of a conspiracy, or at least a trend. That's certainly relevant today. We deal with domestic bombings and shootings and other acts of mass murder on a more frequent basis. There's no conspiracy, but it sometimes seems worse than a conspiracy. There's the sense that something bubbles up from our primordial soup. Something swells in the zeitgeist that provokes these men to what they think is revolutionary zeal or psychic self-defense or protection of some perceived birthright, or a primal scream at a perceived cosmic injustice. No arrest was ever made, but there was a suspect who died before he was arrested. If he was indeed the arsonist, and if the suppositions we can make about his motives are correct, then a straight line can be drawn from his act of violence to the mass gun violence we see today: angry young men with severe depression who for some reason come to feel terribly slighted by life, or by their communities, or both. In this case, it may have been homophobia, but homophobia turned on oneself. I wonder if what we call homophobia is really "femophobia" some fear of losing one's manhood or being thought of, or thinking of oneself, as a woman. As not masculine enough. As a failure as a man. Certainly that would have been in play for the suspect. We continue to grapple with violence with why men (and it always seems to be men) turn into mass killers. The history of the Up Stairs lounge provides few answers, but it does remind us that the history of mass violence in the U.S. is not a short one. It gives us an opportunity to reflect on what messages we send to our young men and boys as we raise them. |

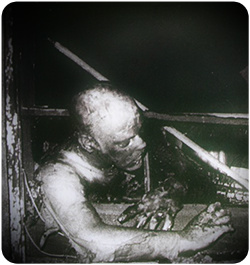

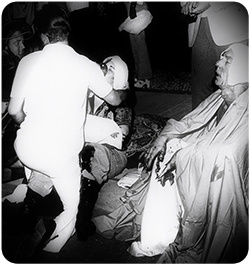

Eighteen-year-old Clancy DuBos, a University of New Orleans student and intern at the Times-Picayune, arrived at the scene as bodies were

being taken out. "I saw bloodstains on the sidewalk and a man sitting in the gutter with his skin burned off, crying he was in such pain" DuBos

remembers, "And there was the sight of that man pressed between the bars of the window trapped and burned there". The Times Picayune headline

the next morning was "29 killed in Quarter Blaze". The States Item's, the afternoon paper, headline was "13 fire victims are identified".

Eighteen-year-old Clancy DuBos, a University of New Orleans student and intern at the Times-Picayune, arrived at the scene as bodies were

being taken out. "I saw bloodstains on the sidewalk and a man sitting in the gutter with his skin burned off, crying he was in such pain" DuBos

remembers, "And there was the sight of that man pressed between the bars of the window trapped and burned there". The Times Picayune headline

the next morning was "29 killed in Quarter Blaze". The States Item's, the afternoon paper, headline was "13 fire victims are identified".

Roger Nunez was picked up for questioning

and he almost immediately went into convulsions. He was taken into Charity hospital, but soon disappeared. He was seen later in the French Quarter

but was never picked up again for questioning. The police and fire marshal at the time concluded that it was an "act of arson".

Nunez committed suicide a year later. Five days after Nunez's death a friend told investigator that Nunez had told him drunk on four occasions,

that he had set the fire. According to his friend, Nunez squirted the bottom steps with Ronsonol lighter fluid and tossed in a match. He didn't realize,

he claimed, that the whole place would go up in flames. The case was left open until 1980 when a spokesman for the fire marshal's office, Glenn Fontenot,

said "After the suspect committed suicide they felt like they'd run out of active criminal leads".

Roger Nunez was picked up for questioning

and he almost immediately went into convulsions. He was taken into Charity hospital, but soon disappeared. He was seen later in the French Quarter

but was never picked up again for questioning. The police and fire marshal at the time concluded that it was an "act of arson".

Nunez committed suicide a year later. Five days after Nunez's death a friend told investigator that Nunez had told him drunk on four occasions,

that he had set the fire. According to his friend, Nunez squirted the bottom steps with Ronsonol lighter fluid and tossed in a match. He didn't realize,

he claimed, that the whole place would go up in flames. The case was left open until 1980 when a spokesman for the fire marshal's office, Glenn Fontenot,

said "After the suspect committed suicide they felt like they'd run out of active criminal leads".